Web Workers rise up!

Introduction

Picture this. You are the dear leader of the little-known land of ScravaJipt, reigning supreme over all you survey. You have a chief servant to look after you, buy your clothes, press the buttons on your mobile phone. But there are times when this gets too much for him. He gets overloaded with all those chores so you have to outsource certain tasks to specialists (one to press buttons, one to buy shirts, another to buy trousers). Luckily for him, there are plenty of workers you can rely on. Similarly, luckily for web developers there are digital specialists that can take over certain tasks when our JavaScript engine gets overloaded. Meet Web Workers, one of many technologies that, together with HTML5, are forming the next generation of the open web.

The raison d'être of Web Workers

Have you ever been to a page that displayed partially but didn't respond to any clicks? Or a page that froze or crashed your browser?

The cause was most likely JavaScript. Web pages are becoming increasingly JavaScript-heavy, sometimes so heavy they can't move. JavaScript's ubiquity is a boon for developers but this means it can run on a wide variety of devices including many that are underpowered for today's web applications. There are several ways to optimize your JavaScript but it still won't be anywhere near as fast as native code.

Web developers are not going to (and shouldn't have to) cut back on their use of JavaScript because of this. Instead, web standards and the browsers that implement them are stepping up to carry the burden. Web Workers are one example of this, together with various other JavaScript APIs that are being developed to bring more power to the browser.

How Web Workers work

Most modern programming languages are multi-threaded, meaning they can run several processes simultaneously. Making JavaScript multi-threaded would require a lot of architectural changes and fundamental re-thinking, so Web Workers offers a way around this, enabling the language to be extended so that it can appear to be multi-threaded in certain cases. In other words, more than one process can effectively be run simultaneously but with some restrictions. Quite a lot of restrictions, in fact, so they're only useful in certain situations.

When can I use them?

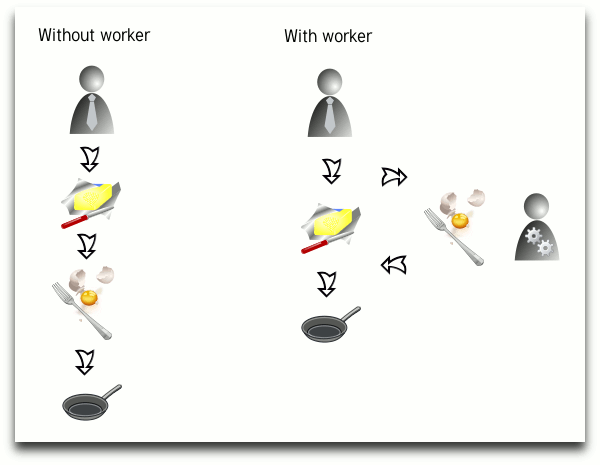

Going back to our 'specialists' analogy, Web Workers can only do one thing but they do it very well. They are excellent at doing fast calculations but are unable to do more complex work such as accessing the DOM. If we compare our web application to a kitchen, the main JavaScript thread would be the head chef about to make an omelette. If he did everything himself, he would beat an egg, prepare a pan, melt some butter and finally cook the omelette. If he wanted to improve efficiency he could get help from a kitchen worker. The worker could beat the egg, enabling the head chef to get the pan and butter ready and then cook the omelette. The worker is not allowed to touch the pan or cook the omelette — he just completes a task while the head chef continues with other work.

Using Web Workers is the same. If your JavaScript includes some resource-intensive calculations, you can pass this to a Web Worker to process while the main thread continues running. You can use more than one Web Worker, and a Web Worker can do more than one task. Let's cook up an example to see it in action.

Just show me the code!

Stay calm, we're getting there! The worker itself is simply some JavaScript code in its own file. Just as the concept of Web Workers is executing code in a separate thread, so the worker code itself has to be in a separate file, or multiple files if you're using more than one worker. In our example, let's start by creating an empty text file and naming it worker.js.

In our main JavaScript thread we use our worker by creating a new Worker object:

var worker = new Worker('worker.js');Like our kitchen assistant, we pass the worker something, it does something with it in the background, and then gives us something back. Communicating with the worker is done using the postMessage method:

// Create a new worker object

var worker = new Worker('worker.js');

// Send a simple message to start the worker

worker.postMessage();It's also possible to pass a variable to the worker:

// Create a new worker object

var worker = new Worker('worker.js');

// Send a message to start the worker and pass a variable to it

var info = 'Web Workers';

worker.postMessage(info);In the worker, i.e. within worker.js, we use the onmessage event to receive the message from the main thread and do something. If you're passing a variable, you can access it with event.data like so:

// Receive the message from the main thread

onmessage = function(event) {

// Do something

var info = event.data;

};Sending messages from the worker back to the main thread uses the same methods:

// Receive the message from the main thread

onmessage = function(event) {

// Do something

var info = event.data;

var result = info + ' rise up!';

postMessage(result);

};// Create a new worker object

var worker = new Worker('worker.js');

// Send a message to start the worker and pass a variable to it

var info = 'Web Workers';

worker.postMessage(info);

// Receive a message from the worker

worker.onmessage = function (event) {

// Do something

alert(event.data);

};Feel free to download this Web Workers demo.

Opera is built as a single-threaded browser with support for a wide variety of platforms, so our current implementation of Web Workers interleaves code execution in the single UI thread. Other browsers, however, may have multi-threaded architectures which enable simultaneous execution of code.

Things to bear in mind

This is obviously a very simple example, but when you give the worker more complicated tasks to do, such as handling large arrays or calculating points in a 3D space for the main thread to display, it becomes a very powerful feature. The main thing to remember, however, is that the worker cannot access the DOM. In the above example, for instance, we could not call alert() within the worker, or even document.getElementById() — it can only receive and return variables, although these could be strings, arrays, JSON objects, etc.

Here's a summary of what Web Workers do and don't have access to.

- Can use:

navigatorobjectlocationobject (read-only)importScripts()method (for accessing script files in the same domain)- JavaScript objects such as

Object,Array,Date,Math,String XMLHttpRequestsetTimeout()andsetInterval()methods- Can't use:

- The DOM

- The worker's parent page (except via

postMessage())

Browser support

At the time of writing, not all browsers support Web Workers so they should be used with care. Rather than trying to keep track of which browser versions do and don't have support, it's easy to include a check within your script. To detect whether a user's browser supports Web Workers, you can test for the existence of the window object's Worker property:

// Check to see if Web Workers are supported

if (!!window.Worker) {

// Yay, I can delegate the boring stuff!

}Web Workers are particularly suited for situations where you don't want to keep the user waiting while some code is processed. The main thread could concentrate on dealing with the UI, displaying it as quickly as possible, while the Web Workers could process the data, using AJAX to communicate with the server, in the background. Everybody's happy, and all is well in the land of ScravaJipt.

Further links about Web Workers

- The latest published version of the Web Workers specification

- A simple Web Workers demo, by Remy Sharp

- Connecting the Dots with Web Workers Example, by Brandon Aaron

- Introducing the Web Workers API, by Nicholas C. Zakas

- Detecting support for HTML5 and related JavaScript APIs, by Mark Pilgrim

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

Comments

The forum archive of this article is still available on My Opera.

-

good intro to web workers. another nice feature of HTML5!

-

Can you help me to process application face detection with getUsermedia on webworker, on my project i use ccv.js and face,js to detect, This is my code using two library:

No new comments accepted.Isuru Nanayakkara

Thursday, January 12, 2012

xuanchien247

Thursday, June 14, 2012

var comp = ccv.detect_objects({ "canvas": ccv.grayscale(App.canvas), "cascade" : cascade, "interval": 5, "min_neighbors": 1 }); for(var i = 0; i < comp.length; i++) { ctx.lineWidth = 2; ctx.strokeStyle = "rgba(255, 5, 0, 255)"; // Stroke rect around region face detect ctx.strokeRect(comp[i].x, comp[i].y, comp[i].width, comp[i].height); }Thanks you so much.