Simple HTML5 video player with Flash fallback and custom controls

Article adapted from original published in .net magazine July 2010 issue. Thanks to Dan Oliver and team!

Introduction

Want to put video onto your web page? HTML5 enables us to do

this as easily as placing images with an <img> element – and in

this tutorial, we’ll show you how the magic is done.

Video basics

Let's start by looking at a basic example:

<video src="video.webm" controls poster="video.jpg" width="854"

height="480">

<p>Your browser can’t play HTML5 video. <a href="video.webm">

Download it</a> instead.</p>

</video>The src attribute points to the video file and

controls indicates that we want the browser to show control buttons (play/

pause, volume and so on). The value of the optional poster attribute is the

path to the static image that the browser will show while the video is loading

and before a user hits play. It’s a good idea to pick an appealing frame from the video or related image that

will persuade users to view the video. If you don’t use poster, the first frame

of the video will be displayed. The code between the opening and closing

<video> tags is fallback content for browsers that have no HTML5 <video> support.

As you can see, the syntax here is beautifully simple. Well, that’s the theory. To

have real cross-browser video, we need to include two files: one encoded as

WebM (which Opera, Firefox and Chrome supports) and one in H.264 format (supported by Safari and IE9). To specify more than one source for a

video element, we drop the src attribute and instead include all the alternative formats with <source> elements:

<video controls poster="video.jpg" width="854" height="480">

<source src="video.mp4" type="video/mp4">

<source src="video.webm" type="video/webm">

...

</video>Note: It is advisable to put the MP4 source first, because of an iPad bug that stops it finding the source, if this is not the case.

The type attribute in this case tells the browser about the

container format (and optionally the codec) of the video. See the source element specification for more details.

Creating WebM videos: For a simple and easy to use application for converting videos to WebM (and many other formats), check out the Miro video converter.

Serving Flash to older browsers

For extra compatibility with less recent browsers, let’s put

the old-style Flash embedding code inside the <video> element

as fallback, so that if the browser doesn’t know anything about

the beauty of HTML5 native video, it defaults to the Flash fallback content

inside the tags.

Flash supports playback of H.264 video, so all we need is our ready-made Flash player (inside the same folder), and we’ll pass it the URL for the H.264 version of our video as a parameter. It’s important to note that the path to the MP4 needs to be either absolute or relative to the location of the SWF file – for simplicity, we’ve placed the player and the videos in the same directory.

<object type="application/x-shockwave-flash" data="m/player.swf"

width="854" height="504">

<param name="allowfullscreen" value="true">

<param name="allowscriptaccess" value="always">

<param name="flashvars" value="file=video.mp4">

<!--[if IE]><param name="movie" value="player.swf"><![endif]-->

<img src="video.jpg" width="854" height="480" alt="Video">

<p>Your browser can’t play HTML5 video. <a href="video.webm">Download

it</a> instead.</p>

</object>So, if we combine all of this together, our final code looks like this:

<video controls poster="video.jpg" width="854" height="480">

<source src="video.mp4" type="video/mp4">

<source src="video.webm" type="video/webm">

<object type="application/x-shockwave-flash" data="player.swf"

width="854" height="504">

<param name="allowfullscreen" value="true">

<param name="allowscriptaccess" value="always">

<param name="flashvars" value="file=video.mp4">

<!--[if IE]><param name="movie" value="player.swf"><![endif]-->

<img src="video.jpg" width="854" height="480" alt="Video">

<p>Your browser can’t play HTML5 video. <a href="video.webm">

Download it</a> instead.</p>

</object>

</video>

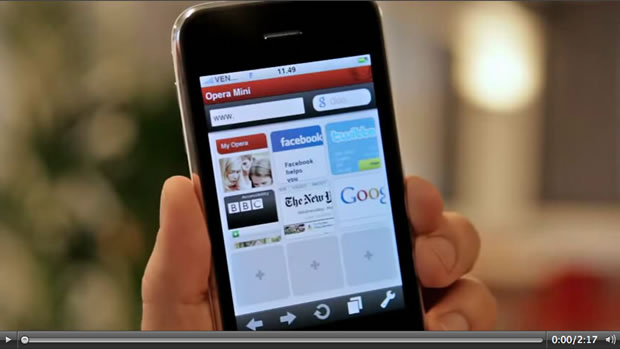

Figure 1: Our video has been encoded as both WebM and H.264 – with a Flash fallback for good measure – giving it real cross-browser compatibility.

See the basic HTML5 video example.

Make your own controls

Everything looks fine now: older browsers will show the Flash player, modern

browsers will use their native video capabilities to show whichever format

video they can support. Because our <video> element has the controls attribute

set, browsers with native video will use their default playback controls. For

many people, that will be enough – but it might be a problem that the default

controls look slightly different from browser to browser, or don’t fit in with the

design of your site. So, let’s try to create our own HTML-based controls that can

manipulate the video via JavaScript.

We’ll keep it simple and just include a Play and Mute button. The most

logical choice for these is to use the trusty <button> element with

corresponding text inside. We’ll add these into the DOM using script, so users

without JavaScript won’t be bothered with the functionless buttons that they’d

get if we put these elements in the markup. For a similar reason, we’ll continue

to specify the controls attribute in the markup and remove it with our script, so

native controls remain available for users without scripting capabilities.

There are nine steps to our script:

- Check for video support

- Get all video containers on the page

- Get every single video instance

- Get and create all needed elements

- Turn off native video controls

- Customise Play button behaviour

- Customise Mute button behaviour

- Add custom controls to the video container

- Initialise function on page load

<script>

function init() {

// 1. Check for video support

if( !document.createElement('video').canPlayType ) return;

// 2. Get all video containers on the page

var videos = document.querySelectorAll( 'div.video' ),

videosLength = videos.length;

// 3. Get every single video instance

for( var i=0; i < videosLength; i++ ) {

var root = videos[i];

// 4. Get and create all needed elements

video = root.querySelector( 'video' ),

play = document.createElement( 'button' ),

mute = document.createElement( 'button' );

// 5. Turn off native video controls

video.controls = false;

// 6. Customise Play button behaviour

play.innerHTML = play.title = 'Play';

play.onclick = function() {

if( video.paused ) {

video.play();

play.innerHTML = play.title = 'Pause';

} else {

video.pause();

play.innerHTML = play.title = 'Play';

}

}

// 7. Customise Mute button behaviour

mute.innerHTML = mute.title = 'Mute';

mute.onclick = function() {

if( video.muted ) {

video.muted = false;

mute.innerHTML = mute.title = 'Mute';

} else {

video.muted = true;

mute.innerHTML = mute.title = 'Unmute';

}

}

// 8. Add custom controls to the video container

root.appendChild( play );

root.appendChild( mute );

}

}

// 9. Initialise function on page load

window.onload = init;

</script>

Figure 2: All it takes to control a video is some straightforward JavaScript. Here we’ve added two basic buttons, one to play the video and one to mute the sound.

See the HTML5 video example with JavaScript controls.

Stay tuned for style

Now we can control a video with nothing more than some simple JavaScript. The buttons work fine, but they don’t look much better than the native video controls. However, before we start doing some styling, let’s add all the necessary classes to our buttons via JavaScript:

play.className = 'video-button video-play';

play.onclick = function() {

if( video.paused ) {

…

// Additional class names for container and button while playing

root.className += ' video-on';

play.className += ' video-play-on';

} else {

…

// Remove additional class names for container and button in paused state

root.className = root.className.replace( ' video-on', '' );

play.className = play.className.replace( ' video-play-on', '' );

}

}Our buttons will be square but, with some tricky rounded corners (using the

much-loved border-radius property, set to exactly half of the width/height of the square), we’ll style them to look like circles:

.video-play {

border-radius:25px;

}Let’s add more dimensions with the box-shadow property, specifying all necessary values separated by commas, with the help of the inset keyword:

.video-play {

box-shadow:0 0 50px #FFF,

inset 5px 5px 20px #444,

inset 0 -20px 40px #000;

}Now, let’s place a small icon under every button to show its current state:

Play/Pause and Mute/Unmute. We’ll add it via CSS-generated content placed

after each button with the ::after pseudo-element (the double colon is newer syntax; we’ll use a single colon for backwards compatibility):

.video-button:after {

position:absolute;

background:url(buttons.png) no-repeat;

content:'';

}To reduce HTTP requests across the network, we’re using CSS sprites: all icons

are put inside a single image, which is placed using background-image and will

be moved by the background-position property according to our needs. But

there’s another niggle: Firefox has a problem with a positioning bug. For some

reason, it thinks the position origin should be in the middle of the element,

while the rest of the browsers are (rightly) basing the positioning coordinates

on the top-left corner. For this reason, we just can’t position our icons correctly

in Firefox – let’s hope this bug gets fixed soon.

So, at the moment there are three browsers that will show our experiment properly: Opera, Safari and Google Chrome. It’s acceptable in our case because we’re just trying things out. After all, we don’t need the other visual niceties.

There’s only one thing left to add – more eye candy. For example, we can make the video semi-transparent in the beginning, less transparent on hover and completely opaque while playing. The background colour of the container is the colour our semi-transparent video will be dissolved in.

.video video {

opacity:.4;

}

.video:hover video {

opacity:.6;

}

.video-on video,

.video-on:hover video {

opacity:1;

}Our experiment wouldn’t be complete without some fancy animations. Let’s

add a couple of properties from the draft CSS3 transforms and transitions

specifications to make our interface and video pop: a smooth increase of the

buttons’ size on hover, and animation of video transparency changes. We’ll

start with the buttons: using the transform:scale(…) property we increase the

button size on hover by an extra 10%. First, we define a button’s default scale:

.video-button {

transform:scale(1.0);

}For full compatibility we should repeat this property four times with vendor

prefixes: -o- for Opera, -webkit- for Safari, Chrome and other Webkit-based browsers, -moz- for Firefox

and other Gecko-based browsers, and one property without any prefixes for future

browsers that will support this property. Next, we define the animation itself. We use the transition property to

smoothly animate changes on any of the button properties for 0.2 seconds with linear acceleration.

.video-button {

transition:all .2s linear;

}Lastly, we define the property that needs to change when the button is hovered. In our case, the size increase by 10%:

.video-button:hover {

transform:scale(1.1);

}We use a similar approach to define all the different states of video transparency that we want to display. Now we have luxuriously styled video that reacts nicely to the user’s actions and is controlled by smoothly animated buttons. And all of this using only pure HTML, CSS and JavaScript, without any plug-ins (except for the small concession of using a Flash fallback for non-supporting browsers.)

Figure 3: We’ve jazzed our buttons up with CSS sprites, border-radius and some outer and inner shadows, ad we've used a transparency trick and transitions to make the interface seem more responsive.

See the final HTML5 video example with CSS facelift.

Why support WebM?

The web that we know and love is built on free and open standards. Web pages are made of HTML, CSS, SVG and JavaScript – all open standards that nobody owns. There are no royalties to pay and no expensive programs to buy; anyone can author with software no more sophisticated than a text editor. That’s vital to the health, continued growth and democratic tradition of the web. HTML5 is a W3C standard with features that, for some use cases, can start to compete with proprietary formats such as Flash or Silverlight. One of these new features is the support for native audio and video playback, giving browsers the ability to display multimedia-enriched pages without the need for any kind of plug-in or royalties.

H.264 on the other hand is a royalty-encumbered format licensed by an organisation called MPEG-LA – two of the licensors are Apple and Microsoft. For a browser to include decoding software, it must pay the MPEG-LA up to $5million a year, based on the rates set for 2010. This high, variable cost is a huge barrier to any new innovative browser entering the market. So what about web developers: do we have to pay a royalty when we use a format to put video on the web? With WebM, you don’t: it’s open. With H.264, you don’t either, if your videos are free for the audience to view (and will always be free). MPEG-LA has announced that it “will continue not to charge royalties for Internet Video that is free to end users … during the next License term from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2015” (see this MPEG-LA press release from 2010). From 2016, they may continue the royalty holiday, or they may charge you whatever they want. If people like us don’t support WebM by including it in our pages – starting now – and H.264 becomes the de-facto standard for HTML5 video, there’ll be nothing at all you can do about it. You’ll have to pay.

On to the browsers. Opera, Firefox and Chrome support WebM. Apple’s Safari and Microsoft IE9 support H.264, with plugins available from Google to help them play WebM. So for the foreseeable future we are looking at a multiple format solution like the one described in this article, at least, until the Flash Player adds support for WebM (Adobe have announced support for VP8, which is the video codec inside WebM, but getting Flash to play Ogg Vorbis, the audio codec inside WebM, is currently a bit tricky).

Read more...

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Comments

The forum archive of this article is still available on My Opera.

-

Html5 can’t replace adobe at once... so that i love html5 fallback support to flash. Because A rapidly growing number of handheld devices support either Flash or HTML5 for video playback. I use Flash Video Player of HD Webplayer to my website with html5 fallback support. HD Webplayer does auto-detect which playback mode is supported by a user's device and select accordingly. It works great for me...

-

Sounds like a good way of doing things, @johnprashath.

No new comments accepted.johnprashath

Friday, December 9, 2011

Chris Mills

Friday, December 9, 2011

I agree that it won't replace Adobe overnight.