HTML5 Drag and Drop

Introduction

HTML5 includes the Drag and Drop API, which gives us the ability to natively drag, drop, and transfer data to HTML elements. Up until now, JavaScript libraries have commonly been used to achieve something similar, such as jQuery UI’s Draggable and Droppable plugins or Dojo.dnd. What libraries such as jQuery UI or Dojo can’t do, however, is interact with other windows, frames, and applications (to and from the file system) or have a rich drag data store.

Marketers like to brand all things HTML5 as shiny and new™ — disappointingly then, the HTML5 Drag and Drop model has roots in Internet Explorer 5 (and below). Ian Hickson, the HTML5 specification editor, reverse engineered the Drag and Drop API from Internet Explorer. The best thing it had going for it was the fact that it was already working in IE, and to some extent Safari and Firefox had implemented it. It may not be the most elegantly designed part of HTML5, but the paths had already been paved.

Before you get too excited, a word of caution: the current cross-browser landscape isn’t pretty. Chrome, Firefox, Safari, and Internet Explorer all implement some form of Drag and Drop, but violate the spec in many different ways. Certain parts of the API, like the dropzone attribute, are only implemented in Opera. Cross-browser drag and drop is going to be tricky (though not impossible) until all the browsers work through their implementation bugs.

Drag and drop is supported now in Opera 12 and to some extent in current versions of Chrome, Safari, Firefox and will be in IE10. With time, we hope all browsers will move towards compatible implementations, or that the spec will be changed to match implementation reality. As always, please remember to file bugs with the browser vendors!

The Drag and Drop API

Without further ado, let’s dive into the main Drag and Drop API features, and see what you can do with them.

The draggable attribute

The quickest way to get started with drag and drop is to add draggable=true to an element.

The draggable attribute indicates to the browser that an element is eligible for dragging with three possible values: true, false, and auto. For example, in the following list of items, the first is draggable, the second isn’t, and the third may or may not be depending on the user agent’s default behavior.

- You can drag me.

- You can't drag me.

- You might be able to drag me.

Keep in mind that text selections are always draggable by default, as are images and links. You can set their draggable attributes to false to prevent this, which may not be very nice for your users.

Here’s the markup for the previous example:

<ul>

<li draggable=true>You can drag me.</li>

<li draggable=false><a href="http://opera.com/">You can't drag me</a>.</li>

<li draggable=auto>You might be able to drag me!</li>

</ul>

The dropzone attribute

The dropzone attribute allows you to indicate in markup where draggable elements may be dropped — and to some extent what to do with them when they are dropped.

The dropzone attribute takes a list of space-separated items with the following possible values: copy, move, link, “string:”, and “file:”.

The copy, move, and link values, which correspond mostly to dataTransfer.dropEffect, indicate the kind of operation that is allowed as the result of a drop.

The string: and file: values allow the author to restrict the type of data that can be dropped by adding a data type— it has to be at least one letter long, and can’t contain spaces:

<div id=droppy dropzone="copy string:text/html file:image/png"></div>This example will put data from text/html content that gets dragged in, or from PNG images dragged from the file system or otherwise obtained via the File API, into the drag data store.

Even with a dropzone element declared, in order to accept a drop the drop target needs to listen for the drop event.

var div = document.getElementById('droppy');

div.addEventListener('drop', doSomethingAmazing);The drag data store

What makes HTML5 Drag and Drop more interesting than a run-of-the-mill JavaScript drag and drop library is the concept of the drag data store. At the core of every drag and drop operation lies a bucket of information that can be passed around. The data store consists of a data store item list, listing each piece of dragged data. These drag items all have a kind (either “Text” or “File”), a type (a string, usually given as a MIME type), the actual data (a unicode or binary string), and some other information that can be used by the browser to give UI feedback.

The dataTransfer object of a drag event is how we get access to read from, write to, and clear the data in this data store. Each dataTransfer object is also linked to a dataTransferItemList object (accesible via the items getter), which contains one or more dataTransferItem objects (accessible via the index of the dataTransferItemList object).

Drag and drop events

Drag and drop introduces seven new events that HTML elements can listen for, all of which bubble. With the exception of dragleave and dragend, they are all cancellable.

Drag and drop events are basically mouse events with a data store. Note that you can both read and write to the data store during a dragstart event, but it is read-only during drop.

For items that are dragged, the events are:

dragstart: dispatched when the user begins dragging a draggable element (or selection).drag: dispatched when the draggable element is moved during a drag (e.g., with the mouse).dragend: dispatched when the user ends the drag and drop operation.

For any element that may receive a drop, the events are:

dragenter: dispatched when a draggable object is first dragged over an element.dragleave: dispatched when a draggable object is dragged outside of an element.dragover: dispatched when a draggable object is moved inside an element.drop: dispatched when a draggable object is dropped.

These are fairly intuitive, but let's examine the event sequence exhibited during a Drag and Drop sequence, to help us understand exactly how it works.

The Drag and Drop event sequence

When the user starts dragging something, the dragstart event fires on the source element, which can be an element with draggable=true set on it, or any elements that are draggable by default, such as links, images, text selections, etc. The dragstart event’s handler can now add data to the data store, to be dropped later on. Once the dragstart event has fired, a series of events fire every few hundred milliseconds, or every time the mouse moves. They are:

drag: firing at the source elementdragover: firing at the current target element

This keeps happening until the mouse passes over a new element. At this point, we see a change: dragenter then fires immediately after the last drag event. If dragenter is cancelled, then this new element becomes the current target, dragleave fires on the previous target to indicate that it is no longer the target, and the dragover event will fire on the new target.

If dragenter is not cancelled, then the <body> becomes the current target. If the dragover event is cancelled as well, then the current target element will be allowed to receive the drop event so the user can now drop the payload being dragged. If not, then dropping will be prevented, as per the spec.

To be compatible with other browsers, we’ve changed our implementation to now allow the element to become the current target even if dragenter is not cancelled. IE still (correctly, per spec) requires this.

So to summarise, the usual repeated event sequence is:

-

drag -

dragenter(if needed) -

dragleave(if the current target has been changed) -

dragover

When the user drops what they were dragging, if dropping was allowed in the last repeated sequence, then drop fires at the current target. The drop event is allowed to see all of the data that was dropped — the only other event that can do so is the dragstart event that created it. If it is not cancelled, then the browser will be allowed to do whatever it would normally do in that case (for example when dropping a file, if you don’t cancel the drop event the browser should try to open the file). After the drag has ended, it fires a dragend event at the source element (even if the drop was not allowed).

This series of events targeted at both the source and target elements allows drags to start in one document and end in another, with both documents being able to monitor the state of the drag. If the drag starts outside the window, or passes from inside it to outside it, then only the events that should be targeted at the relevant document will fire, and the others are assumed to have fired and been allowed or cancelled as needed. If multiple documents are involved, then each receives the relevant events from the sequence.

The effectAllowed and dropEffect properties

dataTransfer.effectAllowed: this determines which of the three "effects" the user will be allowed to choose from when dropping. Possible values are none, all, copy, link, move, copyLink, copyMove and linkMove. The "compound" values like copyMove mean copy or move.

dataTransfer.dropEffect: determines which "effect" will be used when the user drops (or in the case of the drop and dragend events, which one was already used when the user dropped). This will be either the user's choice (if they pressed a modifier key), or the default (depending on what type of element/selection is being dragged), or none (if the user selected a type of drop effect that was not allowed, or dropped somewhere where dropping was not allowed, in which case the drop event will not fire). Possible values are none, copy, link or move.

The script events can also write to this property, to override the user's choice. If the final dropEffect (the last one seen in a dragover event) is not one that is compatible with effectAllowed, the drop will not be allowed (drop event will not fire, dragend event sees "none" as the dropEffect).

So what's the point of all this? The idea is to allow drag and drop scripts to offer functionality like an OS file manager. You know, drag a file from one folder into another. Does it:

- create a "copy" of the file?

- "move" the file?

- create a "link"/shortcut to the file?

The user can choose by pressing modifier keys (they are different on different OSes, but Ctrl, Shift and Alt all do something on Windows). With drag and drop, the idea is that the script looks at the property, and offers relevant functionality. For example, if I offer a remote file manager UI using drag and drop, I can allow the user to press keys to select what should happen, and my script could see what they chose and act accordingly.

Some simple examples

Now we've explored all the theory, let's put it into practice and look at some working examples.

To see the below examples in action, have a look at our Drag and Drop demo.

A simple drag source

The simplest example using the normal events just uses a simple source element (you’ll need to use a link if you want it to work in IE as well) with the draggable=“true” attribute.

<div draggable="true">Ain't life a drag.</div>The draggable <div> should listen for the dragstart event, and put some data into the data store when it is fired. It can also set dataTransfer.effectAllowed, to state whether the user will be allowed to select any of “copy” “move” or “link” using modifier keys. These will be used by the operating system if that’s where the drag ends up, or be passed to the drop handler, if the user chooses a permitted effect that is compatible with the drop target’s dataTransfer.dropEffect property.

<script>

var div = document.getElementsByTagName('div')[0];

div.ondragstart = function (event) {

//browsers may populate the text/html data type for you,

//but Firefox will not allow a drag without setting some data

event.dataTransfer.setData('text/plain','Hello world');

event.dataTransfer.effectAllowed = 'copyLink'; //copy or link

}

</script>Any potential drop target should then listen for and cancel the dragenter and dragover events, and then also listen for the all-important drop event, and in most cases cancel that too. Working with the dropped data is done in the drop event handler.

<div>Drop here.</div>

<script>

var droptarget = document.getElementsByTagName('div')[1];

droptarget.ondragenter = droptarget.ondragover = function (event) {

event.preventDefault();

}

droptarget.ondrop = function (event) {

event.preventDefault();

this.innerHTML = event.dataTransfer.dropEffect + ' ' +

event.dataTransfer.getData('text/plain');

};

</script>Text selections

Dragging text selections is easier to handle. The dragstart event fires at the parent element, but it does not need a handler to create data. The selected text is added as text/plain data. Therefore if we just want to deal with text selections, we can simply remove the dragstart event handler from the above example, and just assume there is some text that the user can select and start dragging.

Microdata

Any microdata items attached to a dragged element, or intersected by a dragged selection, will be included as a JSON string with the mimetype application/microdata+json. When parsed, this is represented as a series of objects and arrays, such as:

parsedJSON.items[0].properties.foo[0] == 'item property data'Currently only Opera supports this.

Files

When files are dropped from the system into a web document (or otherwise obtained via the File API), they appear in the dropped data’s dataTransfer.files collection. Each entry in the collection is a File object, as specified in the File API spec. The contents can then be read using a FileReader object.

<script>

droptarget.ondrop = function (event) {

event.preventDefault();

if( event.dataTransfer.files.length ) {

this.textContent = 'File: '+event.dataTransfer.files[0].name;

var reader = new FileReader();

reader.onload = function () {

var fileAsAString = reader.result;

...

}

reader.readAsBinaryString(event.dataTransfer.files[0]);

}

}

</script>Security

Nothing in the HTML5 specification currently mentions the security implications of drag and drop operations. At Opera, we’ve taken a few measures to make things safer for our users.

Uploads

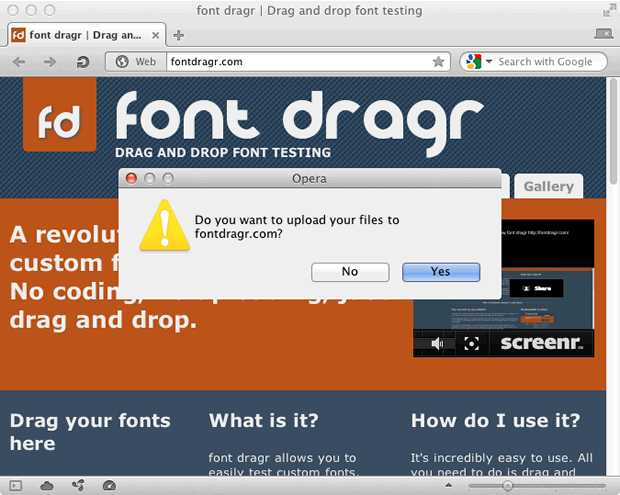

In Opera’s implementation, if a file from the file system is dragged into a page the drop won’t happen unless the user explicitly allows it. Figure 1, taken from fontdragr.com shows an example of this:

Figure 1: Our dialog box, which prompts the user to allow a page to interact with a dropped file from the filesystem.

Exposing event origin

In addition to UI considerations, we’ve proposed (and implemented) the following extensions to event.dataTransfer:

interface DataTransfer {

...

readonly attribute DOMString origin;

void allowTargetOrigin(DOMString targetOrigin);

};dataTransfer.origin is a read-only property that returns the protocol, domain and optional port of the origin where the drag started. If the drag was not started on an origin (such as a dragged file from the desktop), or on a URL that is not a scheme/host/port tuple, the value should be the string value “null”.

dataTransfer.allowTargetOrigin(targetOrigin) defines an origin match for sites which may receive the dropped data. If this method is not called, then all sites and applications may be considered dropzones.

Just like postMessage, dataTransfer.allowTargetOrigin takes one of the three arguments: “*” (matches all origins), “/” (matches current origin), or an absolute URL.

The origin must match permitted target origins on the data store, otherwise the dragenter, dragover, dragleave and drop events are never fired.

dataTransfer.allowTargetOrigin is intended to be used by a site (we can call it the source site) that is putting something sensitive inside the data store, and wants to ensure it will not be leaked to untrusted sites. dataTransfer.origin is intended to be used by a site that will activate a sensitive operation when data is dropped, and wants to ensure that only trusted sites started the drag. That is, it is intended for use by the target site.

To demonstrate this, we've created a sample security page. The top-level window includes the following bit of code:

box.addEventListener('dragstart', function(event){

...

event.dataTransfer.allowTargetOrigin('http://people.opera.com');

});This ensures that the drop can only happen on a document with http://people.opera.com as its origin.

The embedded iframe includes this:

drop.addEventListener('drop', function(event){

event.preventDefault();

if (event.dataTransfer.origin == "http://miketaylr.com") {

var secrets = event.dataTransfer.getData('text');

...

}

});Before we operate on the data, we check the origin of the drop and make sure we trust it.

Both dataTransfer.allowTargetOrigin and dataTransfer.origin may be used, or a site may just use one. It all depends on the use case, and what needs to be protected — the data, the action, or both.

Summary

This concludes our tour of HTML5 Drag and Drop. Pat yourself on the back if you've made it this far, you deserve it. Please let us know what you think in the comments, and help us improve things by submitting bugs.

Resources and Links

HTML Living Standard specification.

Native HTML5 Drag and Drop by Eric Bidelman.

Cross Browser HTML5 Drag and Drop by Zoltan Hawryluk.

DND: compatibility notes by Anne van Kesteren

DND: spec not matching implementations by Anne van Kesteren

DND: proposal to expose origin by Anne van Kesteren

codecompoundThis article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

Comments

-

Once Opera stops opening new tab every time link or image is dragged it is going to be really useful API :)

-

great!

-

Looks delicious :}

-

Thank you for your good explanation of Drag and drop, also thanks to opera team for their good implementation.

No new comments accepted.Martin Kadlec

Thursday, April 26, 2012

Lollo Andersen

Tuesday, May 29, 2012

Tenno Seremel

Thursday, June 14, 2012

Mehdi Shojaei

Monday, October 15, 2012

But I confused why Drag and drop is broken in safari 5.1.7!!! While it works in 4.0.4?