Blob Sallad – canvas tag and JavaScript physics simulation experiment

Blob Sallad is a small demo I put together using the canvas tag, which modern browsers have started

to support in recent versions (eg Opera 9.x and Firefox 2.x,) and some JavaScript physics simulation.

The main inspiration was the game Loco Rocco, and after reading an article about game character physics

by Thomas Jacobsen. I decided I could use similar techniques for

blob simulation.

You can see a working demo of Blob Sallad at http://blobsallad.se/, and download the source code to play around with at http://blobsallad.se/blobsallad.js.

Getting started

To start with, I simply add a canvas tag to my HTML document and gave it a convenient name:

<canvas id="blobs" width="600" height="400"></canvas>In order to draw on the canvas you use JavaScript, for example:

function drawSomething()

{

var canvas = document.getElementById('blobs');

var ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

ctx.lineWidth = 2;

ctx.strokeStyle = "#FF0000";

ctx.beginPath();

ctx.moveTo(10, 10);

ctx.lineTo(40, 10);

ctx.lineTo(40, 40);

ctx.stroke();

}The first two lines in the drawSomething function will find the canvas object using getElementById,

just like with any other HTML object. The second line probes the canvas for its context. The context

is the actual drawing area and as you can see we manipulate different properties of the context such as

line width and stroke color. When you want to start drawing you call use beginPath and move the cursor

around using moveTo and lineTo. When you are done with your path you call stroke and voila. It's all

really simple and Blob Sallad as such doesn't use anything outside the standard API

(see http://developer.mozilla.org/en/docs/Category:Canvas_tutorial for further coverage of the API.)

Animation basics

You will probably want to animate things before long as well. The easiest way to do this is to set up a time-out function in JavaScript. For example:

function mainLoop()

{

drawSomething();

updateAnimation();

setTimeout('mainLoop()', 30);

}First I call mainLoop, which in turn will call drawSomething - this draws the current state on the

canvas, while updateAnimation calculates our object's new position and move it. When all this is done I

call the setTimeout function. Here the first parameter is the function I want to run, namely mainLoop

again. The second is the waiting time in milliseconds, meaning setTimeout will wait 30 milliseconds before

calling mainLoop again. As you can see this will go on forever unless I do something to stop it, but

that's another story.

The physics

Now I have my basic drawing equipment and can cycle an animation forward, the crucial next step is to update the animation. I now need to cover some basics of physics simulation, so you can understand how the blobs in Blob Sallad work - in essence they are made up of point masses and constraints. I will talk about constraints later on; first we will cover point masses.

Point masses

A point mass is an object in two-dimensional space that has properties such as mass and velocity. You can add a force to the point mass to manipulate its speed and direction. The force could for instance be gravity, which would make the point mass fall to the ground.

The following code will move a point mass when I add a force to it. The variable dt is the time step -

the exact value depends on in how large steps you want the animation to update. A larger dt will result

in an animation taking larger steps; a smaller dt will make the animation go slower but smoother. As a

rule of thumb, use a fairly small value, such as 0.05. Values larger than 1.0 will most likely make things

go crazy and 'explode'.

function movePointmass(pointmass, dt)

{

var t, a, c, dtdt;

dtdt = dt * dt;

// move in x-dimension

a = pointmass.force.getX() / pointmass.mass;

c = pointmass.currentPosition.getX();

t = (2.0 - pointmass.friction) *

c - (1.0 - pointmass.friction) *

pointmass.previousPosition.getX() + a * dtdt;

pointmass.previousPosition.setX(c);

pointmass.currentPosition.setX(t);

// move in y-dimension

a = pointmass.force.getY() / pointmass.mass;

c = pointmass.currentPosition.getY();

t = (2.0 - pointmass.friction) *

c - (1.0 - pointmass.friction) *

this.prev.getY() + a * dtdt;

pointmass.previousPosition.setY(c);

pointmass.currentPosition.setY(t);

}The technique used here is called Verlet integration (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verlet_integration for more details.) One of the main advantages of this technique over for instance Euler integration is that it is quiet stable. Complex physics simulation using Euler integration is more prone to 'explode' unless tuned carefully (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euler_integration.) The main reason for this is that the speed of the point mass is implicitly defined by its current and previous position rather than a velocity variable. As long as a point mass doesn't bump into something Euler integrators work ok however updating the velocity of a point mass when interacting with other objects is somewhat complicated. Here I can just move the current position to change the point mass' direction and speed, something that will become convenient when implementing constraints and collisions further on.

In the example above, the variable a keeps track of how much a force will influence the point mass.

Heavy objects need more force to move. The friction part is used when a point mass bumps into something,

for example a point mass in free space would have a friction of 0.1, which would make it slow down after

a while. I've done this because, although it's not completely physically accurate, it often looks better.

If the point mass bumps into a wall you can set the friction to say 0.75 to slow it down a bit. If you

don't do this objects will tend to slide around on floors like as if they where skating around a hockey

rink. The variable t is the new position of the point mass.

Let's talk about walls for a while - what do you do when the point mass hits a wall? It's very simple.

Let's assume that I have a point mass confined to a small room measuring 1 x 1 distance units. I pass the

current position of a point mass as a parameter to the BumpIntoWall function and, if the point mass is on

the outside of the walls, I simply project it to the inside. The method is crude, as I don't take the

point masses' incoming trajectory into account, but if you update in small enough steps (choose a small

dt,) the effect is passable. I really don't care if the simulation is accurate as long as it looks

plausible. After all, JavaScript isn't that fast, so I'd rather save some rendering speed and spend

resources doing other things.

function BumpIntoWall(currentPosition)

{

var collide = false;

var i;

var left = 0.0;

var right = 1.0;

var top = 0.0;

var bottom = 1.0;

if(currentPosition.getX() < left)

{

currentPosition.setX(left);

collide = true;

}

else if(currentPosition.getX() > right)

{

currentPosition.setX(right);

collide = true;

}

if(currentPosition.getY() < top)

{

currentPosition.setY(top);

collide = true;

}

else if(currentPosition.getY() > buttom)

{

currentPosition.setY(buttom);

collide = true;

}

return collide;

}Altering the current position of the point mass as in the example above will also alter its velocity, which is a good thing, recalling the previous discussion about updating velocity. In addition, systems that lose energy in this way often look more realistic. It's really annoying when you see objects on the floor moving around because they are constantly trying to punch through the floor - a typical effect of not losing velocity in the proper manner.

Constraints

A constraint is a rule that states how near or far two point masses can come to each other. In the below example I take two point masses, the black dots, and set them up with a constraint, which is illustrated by the red and blue bars.

For an interactive example, check out http://blobsallad.se/article/example2.html

When the masses get closer to each other than the red bars they wont go any further, as is the case

when they hit the blue bars. How do we know when two point masses actually get too close or to far from

each other? The following code assumes that you understand some basic vector algebra, but I'll try my

best to explain this somewhat simplified version of the satisfy constraints function used in Blob Sallad.

I removed some parts of the code that would make things unnecessarily confusing at this stage. Assume

that we have a constraint with two point masses, pointMassA and pointMassB.

function satisfyConstrains()

{

var delta = new Vector();

delta.set(pointMassB);

delta.sub(pointMassA);

var dotprod = delta.dotProd(delta);

var k = shortConst * shortConst;

if(dotprod < k)

{

var scaleFactor;

scaleFactor = k / (dotprod + k) - 0.5;

delta.scale(scaleFactor);

pointMassA.sub(delta);

pointMassB.add(delta);

}

k = longConst * longConst;

if(dotprod > k)

{

var scaleFactor;

scaleFactor = k / (dotprod + k) - 0.5;

delta.scale(scaleFactor);

pointMassA.sub(delta);

pointMassB.add(delta);

}

}The first thing I did is to create a new vector delta that points from pointMassA towards pointMassB;

it has the same length as the distance between A and B. Then I figure out the squared length of delta

using the dot-product function. The variable shortConst holds the minimum distance the two point masses

are allowed to get from each other. Now, if the squared distance between the point masses (the dot product

of delta) is smaller than the squared shorter constraint, k in this case, the two point masses are pushed

a bit further away from each other. I do the exact same test to see if the point masses are too far away

from each other in the second if statement. If so, they are pushed a bit closer to each other. Read

Thomas Jacobsen's article mentioned above if you want to dig into the details.

Building models

As you might have guessed already one point mass can be shared by many constraints. You can in this

fashion build more complex models by linking together point masses with constraints. As an example assume

that I have three point masses - p1, p2 and p3 - and three constraints - c1, c2 and c3. c1 links p1

and p2, c2 links p2 and p3, and c3 links p3 and p1. This would give me a triangle of point masses linked

together - see http://www.blobsallad.se/article/example3.html for an interactive example of this.

The satisfyConstrains function is used to move p1 and p2 a bit further away from each other if they

get too close. Satisfying c1 might violate constraint c2 because we moved p2 around. Satisfying c2 would

then in turn violate c3, and satisfying c3 would violate c1 and so on. It looks like we have an endless

loop of constraints violating each other going on. In order to solve this in a mathematical manner we

have to solve a system of equations solving all constraints simultaneously. It turns out we don't have

to worry that much though, as the following loop will do the trick:

for(var i = 0; i < 4; i++)

{

c1.satisfyConstrains();

c2.satisfyConstrains();

c3.satisfyConstrains();

}This loop solves the system of equations but in an iterative manner, often called relaxation. The exact number of iterations in the loop is a matter of tweaking. The more iterations, the stiffer an object built this way tends to be. Blobs are not that stiff, so I typically loop over the constraints three to four times. You might wonder why this works, and it took me some time to realize why. It has something to do with the degree of freedom the point masses have when choosing new positions - the solver can typically place them in a position where they don't get in the way of each other (or stated in another way, where it is unlikely that satisfying one constraint will violate another.)

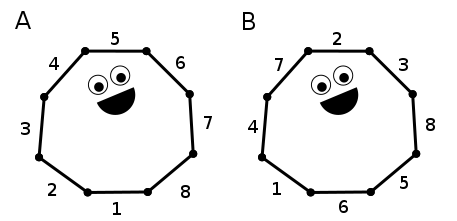

If you, however, try to place the object in a small compartment that can't contain it you will notice strange effects. Also, if you build large objects such as blobs containing say 40 or more point masses they may start moving around in an unpredictable manner. Consider our example blob A below - when solving the first constraint it will push around its' point masses which will make the second constraint move a bit and so on. This creates a 'wave' starting from the first constraint and going through all the constraints back to the first. As the complexity of your models increase the likelihood of one constraint violating another increase, thus creating this 'wave' of going through the model. A simple trick to get around this can be to solve all constraints in a spacial random order, as shown in blob B in Figure 1. This is not exactly fool proof but it can work.

Figure 1: Solving vector constraints in a random order.

However, if such cheap tricks fail you consider solving everything at once using an equations solver. The previously mentioned Wikipedia article about Verlet integration discusses this in some detail.

On to the actual blobs

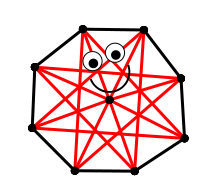

The blobs in Blob Sallad are made of eight point masses as an outer hull, and one point mass in the middle. The point masses of the blob are linked to each other using the constraints described above to make sure the blob will not collapse under it's own weight, as demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: All the point masses of a blob are linked to one another.

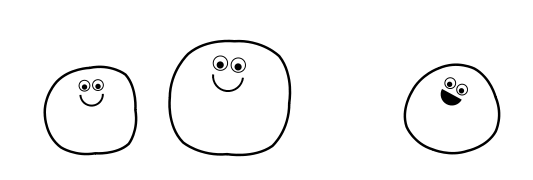

In this set up the blobs looked a bit jagged, so in order to make them more rounded I used Bezier curves in the canvas API to figure out a smooth path around the blob, as shown on the right hand side of Figure 3.

Figure 3: As shown on the right hand side, Bezier curves give a smoother curve round the perimeter of the blobs.

It is not quiet perfect, but using 40 point masses just to get a nice curvy outline isn't an option given the limited computing resources available.

Transformation matrices

One interesting aspect of the canvas API is the ability to draw things in a local coordinate system and then get everything scaled and rotated as an effect of an applied transformation matrix. Confused? Consider the following code snippet used for drawing a blobs' mouth when it is closed.

function drawHappyFace1(ctx, scaleFactor)

{

ctx.lineWidth = 2;

ctx.strokeStyle = "#000000";

ctx.fillStyle = "#000000";

ctx.beginPath();

ctx.arc(0.0, 0.0, this.radius * 0.25 * scaleFactor, 0, Math.PI, false);

ctx.stroke();

}This code simply draws a semi-circle using the arc command. The parameters are x-coordinate,

y-coordinate, radius, start degree and end degree. If I just called this function for every blob all

their mouths would reside at the same place, namely at the x- and y-coordinate origin (0.0, 0.0). Therefore, before

calling this function I need to make the canvas API aware of our current position and somehow make it

draw stuff there instead. This is done using the save, restore, rotate, translate and scale commands.

function drawFace(scaleFactor)

{

// save the current transposition matrix

ctx.save();

// move origo to the middle of the blob

ctx.translate(middleX, middleY);

// rotate everything draw from here on any degrees

ang = figureOutBlobRotation();

ctx.rotate(ang);

// draw the happy face number one

drawHappyFace1(ctx, scaleFactor);

// make everything go back to the point as it was

// when calling save

ctx.restore();

}I first call save, which saves a copy of the current transformation matrix on a stack inside the

canvas tag. A transformation matrix is a mathematical manipulation of sorts. Just think of it as a black box

unless you intend to study linear algebra to find out exactly how it works (it's out of scope for this article in any case.) As a default the transformation matrix associated

with the canvas tag doesn't do anything, but it is always there. I can set up the transformation matrix

to translate, i.e. move things around. For example, if I tell the black box to move everything it gets

by (2.0, 3.0) and I give it the coordinates (1.0, 1.0) it will spit out (3.0, 4.0). In addition you can

tell it to rotate or scale everything it gets as well. The nice thing is that you can make it do all

these things at the same time, without any additional cost or computation time. Great news!

After calling save to remember the current transformation matrix, I then start manipulating it using

translate. I want everything I draw from here on to originate from the middle of the blob - essentially

I set up the coordinate system so that (0.0, 0.0) is in the middle of the blob. Furthermore I figure out

how the blob is rotated around its own axis by calling figureOutBlobRotation. That value becomes an

argument of rotate, and then I call drawhappyface1. This draw function is totally oblivious to the blobs'

orientation, but it doesn't have to know anything - when it calls the arc function the canvas API will

apply the current transformation matrix black box to every coordinate it gets.

When I am done I call the restore method and everything goes back to how it was when I called save,

which is a good thing when calling draw for the next blob. Since transformation matrices are stored on a

stack you could call save, do some manipulation, call save again and so on. When done you just call

restore, draw something else using the previous transformation matrix, call restore and save and so

on until you are back at the bottom.

The observant reader might have noticed that the parameter scaleFactor could have been part of the

transformation as well. I really have no good reason for not doing that except maybe temporary insanity.

The Eyes

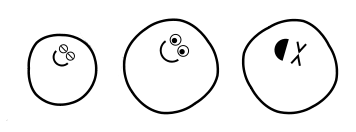

The blobs have three different possible kinds of eye. Open, closed and yihaa! eyes, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: The 3 different kinds of eyes that blobs have - open, closed, and yihaa!.

It's really a matter of switching eye state once in a while. This code snippet is called every frame to randomize between open and closed eyes.

if(eyeStyle == 1 && Math.random() < 0.025)

eyeStyle = 2; // closed eyes

else if(eyeStyle == 2 && Math.random() < 0.3)

eyeStyle = 1; // open eyes

drawEyes(eyeStyle);What are the yihaa! eyes then? When using the arrow keys to move the blobs around really fast they change eye style, and blobs love it when you smash then into walls, really they do! Basically, if the blob moves at a certain velocity it gets the yihaa! eyes. To figure the speed of the blob you can use the current and previous position of the middle point mass. Remembering the previous discussion about point masses, consider the following code.

function getVelocity()

{

var cXpX, cYpY;

cXpX = currentPosition.getX() - previousPosition.getX();

cYpY = currentPosition.getY() - previousPosition.getY();

return cXpX * cXpX + cYpY * cYpY;

}The previous code snippet could be extended to this.

if(getVelocity() > 0.004)

eyeStyle = 3; // the yihaa! eyes

else if(eyeStyle == 1 && Math.random() < 0.025)

eyeStyle = 2; // closed eyes

else if(eyeStyle == 2 && Math.random() < 0.3)

eyeStyle = 1; // open eyes

drawEyes(eyeStyle);If you are familiar with physics you might notice that we actually do not compute the velocity of the

blob in getVelocity but rather the squared velocity. In order to get the actual velocity you would have

to take the square root of the return value. I am, however, only interested in the case when the blob

moves faster than some certain limit not the actual speed. Which means that it doesn't matter if we use

the squared value or not. I guess the lesson here is that you can cheat as much as you want as long as it

looks plausible.

The Blob Collective

The last part is to make many blobs. A container class called a blob collective holds the blobs, and follows some rules. Blobs can't get too close to each other, and in order to make them stay away from each other each blob has a constraint set up between its middle point mass and all the other blob's middle points. This constraint is a special case of the constraints discussed previously, which will allow two point masses to get as far from each other as they want but not too close. The following code will do the job.

function satisfyBlobToBlobConstrains()

{

var delta = new Vector();

delta.set(pointMassB);

delta.sub(pointMassA);

var dotprod = delta.dotProd(delta);

var k = shortConst * shortConst;

if(dotprod < k)

{

var scaleFactor;

scaleFactor = k / (dotprod + k) - 0.5;

delta.scale(scaleFactor);

pointMassA.sub(delta);

pointMassB.add(delta);

}

}As you can see, I simply omitted the second if statement from the previous code, which would try to

move the point masses back towards each other if they were too far from each other. In the case where

they get to close, I move the middle point mass of the blob as before. Please note that I only move the

middle point mass, but the middle point mass is hooked up to all the other point masses of the blob by

a bunch of constraints, so they all drag along. This is somewhat interesting because you can build quite

complex structures using point masses and constraints and then make them interact with each other,

without any additional principles involved.

When the user presses 'h' (the create a new blob key) I find the largest blob available and remove it from the bob collective and insert two smaller blobs. When figuring out the positions of the new blobs I intentionally place them too close to each other so that the keep-away-from-me constraint described before will kick in and make the blobs bounce off each other.

In the same fashion, when joining two blobs I find the smallest one available and the one that is the closest to it and replace them with one larger blob.

Keyboard interaction

To make the blobs move around using the arrow keys is rather easy. First I figure out if an arrow key was pressed.

document.onkeydown = function(event)

{

var keyCode;

if(event == null)

keyCode = window.event.keyCode;

else

keyCode = event.keyCode;

switch(keyCode)

{

// left

case 37:

addForceToAllBlobs(new Vector(-50.0, 0.0));

break;

// up

case 38:

addForceToAllBlobs(new Vector(0.0, -50.0));

break;

// right

case 39:

addForceToAllBlobs(new Vector(50.0, 0.0));

break;

// down

case 40:

addForceToAllBlobs(new Vector(0.0, 50.0));

break;

}

}The code will add a keyboard listener to the document. If an arrow key is pressed the above code will

be executed, adding a force to all point masses of all blobs. These forces point in different directions

depending on the key pressed. A force here is simply a vector of some length. Recall how this influenced

a point mass in the movePointmass function.

Gravity is implemented in the same way; in each frame I add a force pointing downwards to all point masses.

An important note on gravity and forces. As you might know two objects independent of weight and size

will fall towards the earth at the same speed in vacuum. This is because gravity does not act as a force

but rather as acceleration. If we review the code in movePointmass we will find the following line.

a = pointmass.force.getX() / pointmass.mass;The variable a is the acceleration of the point mass, in this case in the x-direction. Clearly the

mass of the point mass has something to with this. Heavier point masses will not be as influenced by a

force as lighter ones. But this is in clear violation of how gravity works. In my case this still works

since I have been a lazy programmer and just made all the point masses weigh the same, namely one weight

unit. But you might want to actually have point masses of different weights and still have working

gravity. To solve this you can either multiply the gravity force for each point mass with the weight of

the point mass.

pointmass.addForceX(gravity.getX() * pointmass.mass);

pointmass.addForceY(gravity.getY() * pointmass.mass);Or you can implement an independent addAcceleration method, which would have to be considered when

moving the point mass.

function addAcceleration(acc)

{

this.acceleration.Add(acc);

}When moving the point mass, I extend the code like this.

a = pointmass.force.getX() / pointmass.mass;

a += acceleration.getX();Mouse interaction

The mouse interaction is a bit more complicated. To find the current position of the mouse I have to add a mouse listener, as sene below (note that I stripped out some error checking in the example below to make it less confusing for now.) When writing a mouse listener you will have to add some tests since all browsers do not behave in the same way (see the Blob Sallad source code for a working example.) First we want to know if someone clicked the mouse.

function getMouseCoords(event)

{

return {x : event.pageX, y : event.pageY};

}

document.onmousedown = function(event)

{

var mouseCoords;

mouseCoords = getMouseCoords(event);

selectOffset = selectBlob(mouseCoords.x, mouseCoords.y);

}When someone presses the mouse I figure out if a blob is being selected by calling selectBlob, which

is a part of the blob collective class. What I want to do is check if I actually clicked on a blob.

function selectBlob(x, y)

{

var i, minDist = 10000.0;

var otherPointMass;

var selectedBlob;

var selectOffset = null;

for(i = 0; i < numBlobs; i++)

{

otherPointMass = getBlob(i).getMiddlePointMass();

aXbX = x - otherPointMass.getXPos();

aYbY = y - otherPointMass.getYPos();

dist = aXbX * aXbX + aYbY * aYbY;

if(dist < minDist)

{

minDist = dist;

if(dist < getblob(i).getRadius() * 0.5)

selectOffset = { x : aXbX, y : aYbY };

}

}

return selectOffset;

}First I loop through all the blobs in the blob collective and check to see if any blobs' middle point mass is closer to the mouse pointer than its radius; if so, the blob is selected. If a blob is selected I let the blob collective remember which one. The select offset is the distance from the middle point mass to the mouse pointer. I use the select offset later when moving the mouse around to avoid making the blob jump to the mouse position, which leads to the next part, what happens when moving the mouse.

document.onmousemove = function(event)

{

var mouseCoords;

mouseCoords = getMouseCoords(event);

selectedBlobMoveTo(mouseCoords.x – selectOffset.x,

mouseCoords.y - selectOffset.y);

savedMouseCoords = mouseCoords;

}In this part I get the mouse position and subtract the select offset. This is to stop the blob

"jumping" to the position of the mouse. Then I call the function moveSelectedBlobTo.

function moveSelectedBlobTo(x, y)

{

if(selectedBlob == null)

return;

var i, blobPos;

blobPos = selectedBlob.middlePointMass.getPos();

x -= blobPos.getX(x);

y -= blobPos.getY(y);

for(i = 0; i < selectedBlob.pointMasses.length; i++)

{

blobPos = selectedBlob.pointMasses[i].getPos();

blobPos.addX(x);

blobPos.addY(y);

}

blobPos = selectedBlob.middlePointMass.getPos();

blobPos.addX(x);

blobPos.addY(y);

}This is pretty straightforward - I have simply added the offset of the mouse to every point mass of the blob. An interesting aspect of this is that you do not have to bother with the velocity of the point mass since that is, again, an implicit result of moving the point mass around in this fashion. As a last measure I have registered the following function, which is triggered when releasing the mouse.

document.onmouseup = function(event)

{

unselectBlob();

savedMouseCoords = null;

selectOffset = null;

}The unselectBlob function simply sets the selected blob in the blob collective to null, which will make

moveSelectedBlobTo to exit early if no blob is selected.

Summary

This article has taken you through some techniques for physics simulation and using the canvas tag.

You can use physics simulation to do many things, such as cloth simulation and moving cars around in game

engines. Don't be discouraged if your simulations explode quite a bit in the beginning. It usually takes

some tweaking before everything is set straight.

Note: I would like to point out that the code examples here are stripped down and simplified, to make them readable and less confusing, so they shouldn't be taken as working examples. My hope is that I have helped you recognize the key principles here, and can go on to implement your own stuff.

Also worth noting is that there is a non trivial part of the Blob Sallad code - handling vector arithmetic - which I have omitted from this tutorial altogether. I think that vectors are pretty well covered elsewhere on the web.

Furthermore, collision detection has not been discussed at all - this is because Blob Sallad doesn't use any. The environment class could be said to do some collision detection but it is hardly anything useful if you want to implement more complicated environments.

Make sure to check out http://blobsallad.se/ for the Cairo + SDL version of Blob Sallad; send me an e-mail if you have any questions (bjoern.lindberg@gmail.com.)

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution, Non Commercial - Share Alike 2.5 license.

Comments

The forum archive of this article is still available on My Opera.

No new comments accepted.