Better performance with requestAnimationFrame

Introduction

This article discusses how you can (and should) improve the performance of your animations, using the requestAnimationFrame API instead of the old setInterval/setTimeout methods, and how requestAnimationFrame is used. And of course, we will show you the mandatory code example of requestAnimationFrame in action.

requestAnimationFrame is now supported across all modern browsers, although still prefixed in some. Erik Möller has written a polyfill that should handle all other browsers. We'll see this in more detail later. Let's start from the beginning...

The not-so-good old way

In order to see what's great about requestAnimationFrame, we must first have a look at the not-so-good old way in which we used to do animations. I'm sure I don't need to tell you that long before Mozilla got the first experimental implementation of mozRequestAnimationFrame you could already create animations using setTimeout and setInterval. I'll assume you're already familiar with these two so I'll not go into details, if you want to know more here's an excellent article by John Resig explaining in depth how JavaScript timers work.

As much as I don't want to be dismissive of these old-school methods, they do have some unfortunate downsides. First of all, JavaScript timers continue to work even in background tabs, and even when the corresponding browser window is minimized. As a consequence, the browser will continue to run invisible animations, resulting in unnecessary CPU usage and wastage of battery life. This is especially bad in the case of mobile devices.

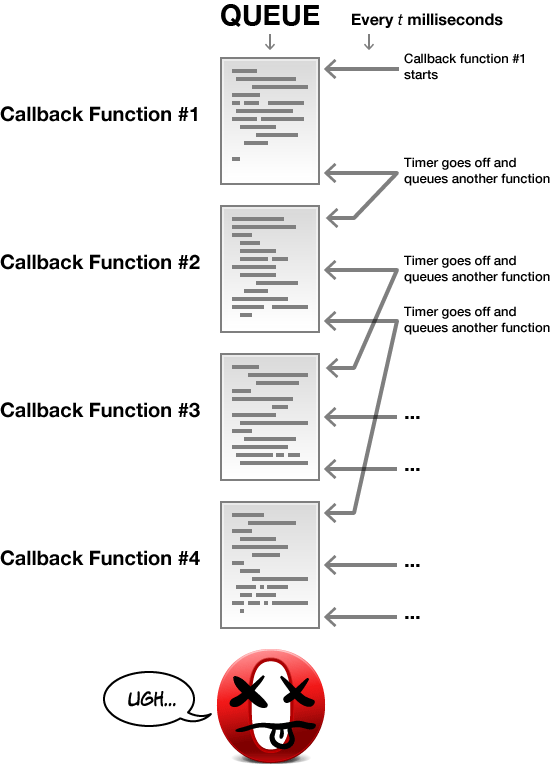

Second, not only do timers continue to run for invisible animations, but when their time is up they also always enqueue their callback functions. Let me explain why this can sometimes pose a problem — say you didn't do your job particularly well and for some reason the callback function takes more time to finish than you have set up your timers for. Once the timers are up they will enqueue yet *another* callback function, even though the previous one hasn't finished running. As this process repeats itself over time, you can quickly enqueue a virtually infinite amount of timer code, causing the browser to stall. Figure 1 provides an illustration of this.

Figure 1: If your callback functions take longer than your timers, enqueuing of multiple callback functions can choke up the browser.

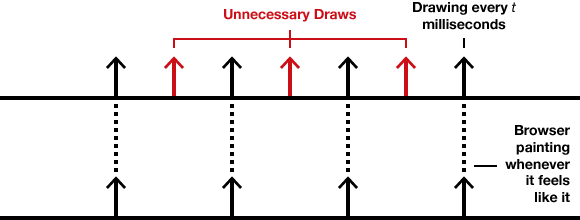

But even in cases where your callback functions don't take longer than the timers, setTimeout and setInterval still aren't optimal. Both can only redraw animations at a fixed rate, so to make sure the animation is smooth, we tend to err on the side of caution and choose a frequency slightly higher than the display refresh rate. This, however, causes unnecessary drawing, as some frames are drawn before the display refresh rate is ready to paint the animation outcome and are therefore just discarded. Figure 2 illustrates this problem.

Figure 2: Skipped frames can lead to higher CPU usage and battery consumption, and sometimes even choppy animations.

These downsides are even more dangerous when these methods are used to implement looping animations, for example in games or crazy experiments like my hipster dog, as looping animations guarantee to endlessly enqueue new callback functions in such scenarios. If you want to read more about the history of looping animations on the web, how animation loops behave when using setTimeout and setInterval, and how requestAnimationFrame has changed the way we code, I recommend you read Better JavaScript animations with requestAnimationFrame by Nicholas Zakas, which deals with the subject in depth.

Introducing requestAnimationFrame

requestAnimationFrame is an API that does exactly what you would hope for: it passes the responsibility of scheduling animation drawing directly to the browser. The browser can do it better because, well, it knows what's going on inside the browser!

requestAnimationFrame is part of W3C's Timing control for script-based animations API.

What requestAnimationFrame does

The browser knows about things like the tab and window status, what parts of a page are visible or not, when the browser is ready to paint, and what other animations are also running and visible. requestAnimationFrame addresses the problems with JavaScript timers we discussed before by putting the browser in charge and allowing it to use this information to optimize animation scheduling. So, the workflow for requestAnimationFrame looks like so:

- First, it only draws the animations that will be visible to the user. That means no CPU power or battery life is wasted drawing animations that are running in background tabs, minimized windows, or otherwise hidden parts of a page.

- Second, frames are only drawn when the browser is ready to paint and there are no ready frames waiting to be drawn. This means that it's impossible for an animation drawn using

requestAnimationFrameto enqueue more than one callback function or to stall the browser. - Third, since frames are only drawn when the browser is ready to paint and there are no ready frames waiting to be drawn, there are no unnecessary frame draws. So animations are smoother and CPU and battery use are optimized further.

I just said no additional callbacks will be enqueued until the current one has finished drawing and has been painted. However, if you call requestAnimationFrame() more than once each call will enqueue one callback, so you'll get additional callbacks.

Also, the browser can have several animations happening in the same page in a single reflow and repaint cycle.

What requestAnimationFrame does NOT do

requestAnimationFrame does not:

- Set up a continuous animation; it only schedules a single update that is identified by an id number returned by that particular request. If subsequent animation frames are needed, then

requestAnimationFramewill need to be called again from within the callback function. If you need to stop the animation, you can usecancelAnimationFrame(id). - Guarantee when it'll paint; only that it'll paint when needed.

- Guarantee the synchronicity of the animations. For example, if you start two animations at the same time but then one of the animations is in an area that is visible and the other is not, the first animation will go on playing while the other will not; when the second one becomes visible again, they may be out of sync. If you care about this you'll have to take care of this when you write your animation code, by making sure that the state of all the animations that need to be in sync is dictated by a parameter that goes unaffected by visibility (like the time passed since the starting time of the animation group, for example) as opposed to depending on each animation's previous frame.

- Paint until the callback function has finished executing, even if you try to trigger a reflow mid-callback by using any of the methods that would trigger a reflow and repaint in normal conditions, like

getComputedStyle(), for example.

How to use requestAnimationFrame

requestAnimationFrame is now supported across all modern browsers but it's still prefixed in some. At the time of writing the (un)prefixing situation is as follows:

- Opera: unprefixed since Opera 15

- Chrome: unprefixed since version 24

- Safari: prefixed

- Firefox: prefixed, although unprefixed as of version 23

- IE: unprefixed since version 10

However, to make sure your code works truly everywhere you should use Erik Möller's polyfill, which provides robust cross-browser support, improving on Paul Irish's fantastic original groundwork on the subject.

Here is the simple code that handles the animation inside our frog demo:

var requestId = 0;

var animationStartTime = 0;

function animate(time) {

var frog = document.getElementById("animated");

frog.style.left = (50 + (time - animationStartTime)/10 % 300) + "px";

frog.style.top = (185 - 10 * ((time - animationStartTime)/100 % 10) + ((time - animationStartTime)/100 % 10) * ((time - animationStartTime)/100 % 10) ) + "px";

var t = (time - animationStartTime)/10 % 100;

frog.style.backgroundPosition = - Math.floor(t / (100/2)) * 60+ "px";

requestId = window.requestAnimationFrame(animate);

}

function start() {

animationStartTime = window.performance.now();

requestId = window.requestAnimationFrame(animate);

}

function stop() {

if (requestId)

window.cancelAnimationFrame(requestId);

requestId = 0;

}requestAnimationFrame is a method that will signal to the browser that a script-based animation needs to be resampled by enqueuing a callback to the animation frame request callback list. This holds a list of the ids of the callback functions that are waiting to be executed. Calling requestAnimationFrame returns the id (requestId) that identifies the callback that has been enqueued. That id can be later used to cancel the callback, by using cancelAnimationFrame(id).

The requestAnimationFrame method takes as its argument the callback that needs to be executed to draw a new frame of the animation (animate). The callback, in turn, is itself a function that receives as an argument the timestamp of when the animation update was requested (time).

This timestamp is the result of invoking the now method of the Performance interface. You need to make sure that any other time measurement you want to compare this with is also a DOMHighResTimeStamp — in the example above we are calling window.performance.now and storing the result in the animationStartTime variable. In the animation function (animate) we then compare this start time with the current time (time) in each frame to calculate the position of the frog in each case.

When coding your animations, in case you bump into some old tutorials, note that the animationStartTime property was built in, but it is now deprecated, so you'll have to keep track of the start time yourself like I've shown above.

To see this code in action, you can have a look at the source of my requestAnimationFrame demo.

Summary

In this article we have discussed how requestAnimationFrame increases the performance of JavaScript animations and how you can use it in a way that will successfully work in all browsers. I hope this article inspires you to try some cool animation experiments — and to update any old animation code you may have lying around!

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

Comments

-

Interesting. I would agree that focusing on growth vs cost control during the early stages of a business is ideal, however, there will be a point when that shifts.

No new comments accepted.ahsanazam

Wednesday, December 18, 2013

Paleo Diet